September 1940. While the Luftwaffe and the RAF fighter pilots fight for control of the skies over England during the Battle of Britain, a close eye is kept on German invasion preparations – Operation Seelöwe (Sealion). An assault on British shores would require the transportation of troops across the English Channel; air supremacy is paramount. The German Navy deems it essential that the Royal Air Force be kept clear of the sea approaches to the south of England. Meanwhile British intelligence maintains a vigil on enemy shipping movements across the narrow sea divide. The evidence is steadily mounting.

On 3 September Bomber Command Intelligence Report No. 908 reports:

Photographs taken 2 Sept show: Off Calais thirty five small motor boats in line astern setting course northwest from neighbourhood Calais harbour. West of Dunkirk eight E boats in line astern proceeding west reported by visual reconnaissance four miles from shore. Increase of fifty barges Ostend since 31 Aug. Increase of one hundred and forty barges at Terneuzen since 16 Aug. No concentration of barges at the north end of Beveland Canal, slight increase since 1 Sept at south end where total is now approaching two hundred.

And in the 7 September report No. 920 photographs taken at 1130 hours that day, show numerous concentrations in ports including:

Ostend: Increase of 100 barges making a total of 300. 30 vessels forty feet in length possibly tugs or motor boats for towing which are also new arrivals. Naval unit 280 feet long possibly coastal defence ship Peder Skram.

Bruges – Ostend Canal: Six tows comprising 33 barges moving towards Ostend.

Dunkirk: In harbour an increase of 45 barges total 75. No change in the barges in the waterways of the town. 32 barges anchored offshore.

Calais: In the harbour are 86 barges, 13 smaller vessels probably for towing and 35 small craft 45 feet. Lying off are 17 barges and 30 small vessels probably for towing.

These are just a few of the intelligence reports detailing enemy shipping movements. Clearly something has to be done, and RAF Bomber Command is tasked with sinking boats and blasting port facilities. The bombing campaign against the build-up of enemy shipping in the channel ports, the ‘Battle of the Barges’ proves instrumental in re-enforcing the fact that the Germans need air supremacy for a seaborne invasion. RAF Bomber Command plays a prominent part fighting this battle.

On 7 September 1940 the Luftwaffe switches focus away from the RAF itself, believing, incorrectly, that Fighter Command’s ability to defend is all but spent. London, becomes the target of a mass daylight raid, and that night further Luftwaffe raiders have no trouble finding the burning city and stoking the fires. On the evening of 7 September the code-word ‘Cromwell’ is issued – invasion imminent. It is time to focus attention on the enemy occupied ports.

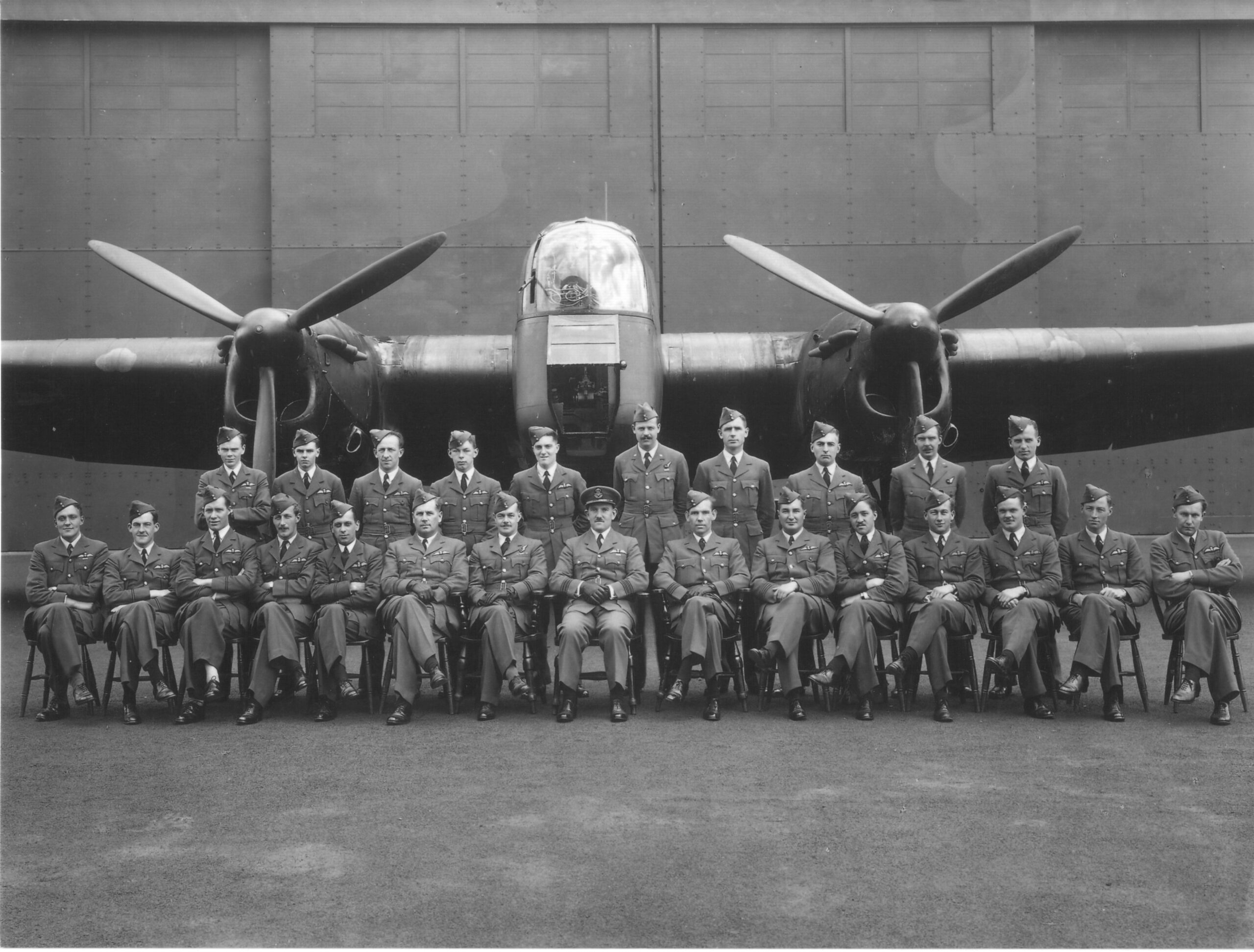

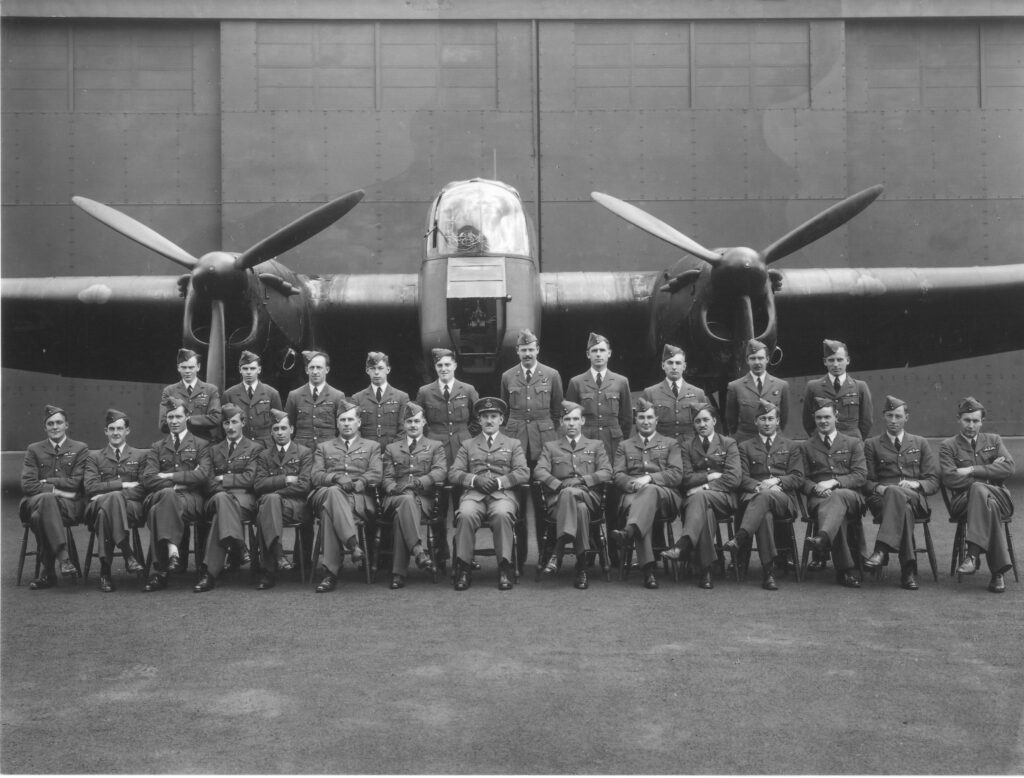

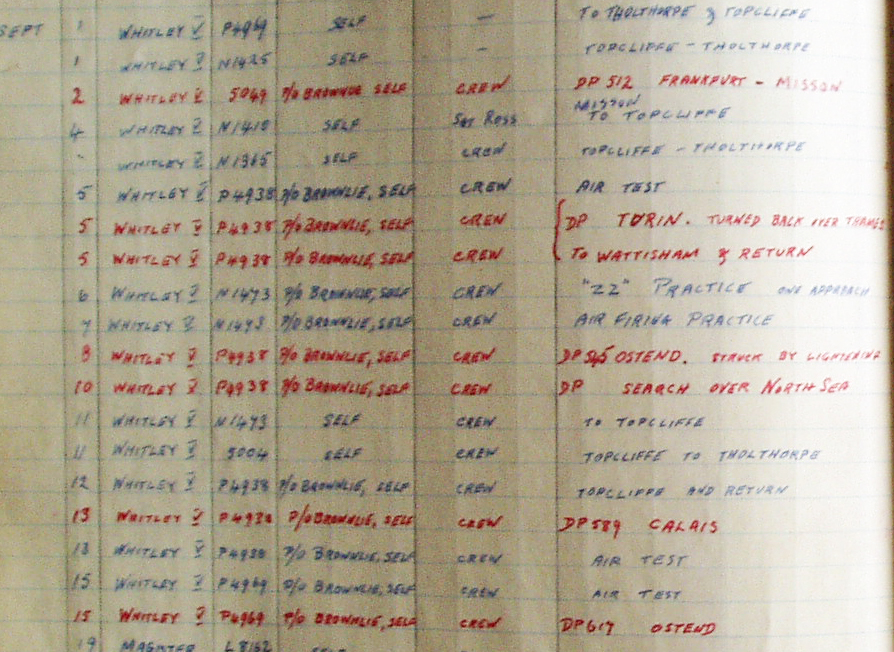

Richard Pinkham flying as a second pilot to Pilot Officer Ian Brownlie, on Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys with No. 77 Squadron, recalls one such raid as part of the Battle of the Barges.

8 September 1940. There was a big ‘flap’ on, as reports came through that Jerry was preparing an invasion fleet of landing barges in preparation for landing their army on the south coast. If only Hitler had realised how weak our defences were, if he had gone ahead with an invasion, he could probably have succeeded. But he did not. We had to destroy those landing barges, which were assembling in the Channel ports. We were detailed to hit the harbour at Ostend.

The weather was appalling, but it was one of those occasions when you don’t let a little weather stop you. We had to fly through a lot of thunderstorm clouds, and the night was lit by spectacular flashes of lightening. The clouds were full of static electricity, which charged the aircraft and produced St. Elmo’s light. All the extremities of the aircraft, the propeller tips, the wing tips, glowed with a bright light. Ships at sea experience this phenomenon, which looks very ‘pretty’, the result of static being discharged quite harmlessly, nevertheless fascinating to watch.

I was standing beside the pilot, watching the propeller tips form arcs of light, lighting up the aircraft like a Christmas tree. As the lights grew, the noise of the static in the intercomm also got louder, a crescendo. The lights were getting brighter when suddenly there was a blinding flash and deafening crack. We had been struck by lightning. My immediate reaction was ‘this is it, any moment now we will be falling out of the sky!’ Instinctively I put my hand over my eyes, and uttered a prayer, ‘Look out God, here I come.’ After seconds passed, nothing had happened, and we were still flying straight and level. The skipper called up on the intercomm, ‘Everybody alright?’ Each replied that they were ‘OK skipper’. ‘Let’s press on then’ uttered the skipper.

Thunderstorms are usually fairly local and concentrated, so after a while we broke clear sky, just in time to see the Dutch coast coming up. We were able to pick out the target without any difficulty, sailed right in and dropped a ‘stick’ of bombs right across the target and high-tailed it back home. On the way back the ‘Wop’ tried to get a fix and discovered that the trailing aerial had been burnt off by the lightning. Reeling in the aerial he found a short length with a melted blob at the end! Had he wound the aerial in before entering the storm, as he should have done, the lightning would have passed through the aircraft somewhere else, where it could have had much more serious consequences. As it was the lightning discharged harmlessly. That night, one of our aircraft was missing, believed to have gone down in the ‘drink’. Next morning every aircraft was sent to do a search of the North Sea. Each aircraft was detailed for a separate grid, in which each one would carry out a square search. It is unbelievable how difficult it is to pick out a yellow rubber dinghy in a vast expanse of sea. We had to fly at 1,000 feet, as there would be little chance of spotting anything from any higher. We continued the search for six hours, but saw nothing. There was always the possibility of encountering fighters, but with complete cloud cover we were reasonably ‘safe’. None appeared.

The night of 8/9 September 1940 has been a busy one for Bomber Command, sending 133 aircraft to targets at Hamburg, Bremen, Emden, Ostend and Boulogne. Eight aircraft fail to return from these operations, one of those being lost on the attack on the Blohm and Voss shipyards in Hamburg, with the Hampden crew of four all taken prisoner. Three Blenheims are lost on the Ostend raid and two Blenheims and two Wellingtons fall from the sky on the Boulogne raid. There is only one survivor from the crews lost attacking the Channel port targets; 26 airmen have been killed. The bodies of five of these men are found and buried. The remaining 21 airmen are lost without trace, probably in the English Channel, their names commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

The Battle of the Barges continues over the following weeks and months. The relative success of the campaign is a key factor in hindering German invasion plans and ambitions, but many RAF Bomber Command airmen pay the ultimate price.

(Wing Commander Richard Pinkham DFC flew 62 bombing operations during the Second World War. He tells his story in the book On Wings of Fortune – A Bomber Pilot’s War, co-authored with Steve Darlow.)