One of the least recognised contributions by Bomber Command to Operation Overlord and the success of the D-Day landings was the arming of the French Resistance in the run up to 6th June 1944. When writing my book ‘D-Day Bombers’ I had the pleasure to work with 90 Squadron Stirling pilot Dennis Field.

On this day 80 years ago, Dennis lifted his Stirling from the RAF Tuddenham runway on an operation to supply the Resistance, and what follows is an extract from the book recounting the dramatic and tragic events that night.

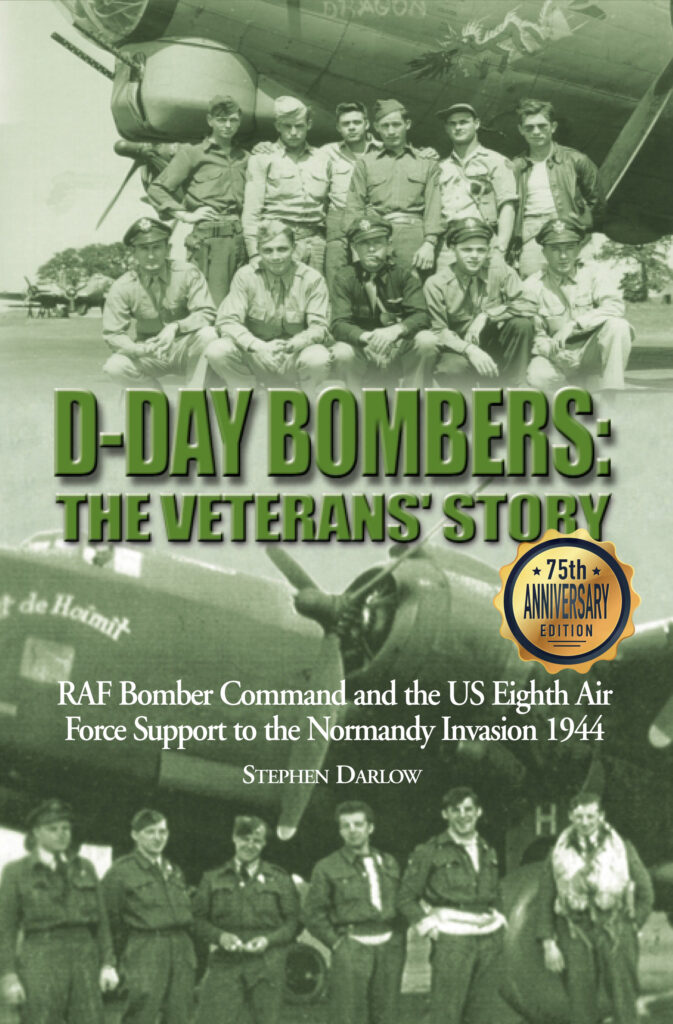

(Signed copies of the D-Day Bombers book are available here.)

For the April moon period the first priority for assisting the French Resistance had been to make arms drops north of the line Nantes-Orleans-Dijon-Strasbourg, an obvious move to strengthen the Resistance networks, which could directly engage the German reinforcement that would be sent to the Normandy invasion area. The remainder of France, including the Maquis, would be given second priority. Eventually of the 516 sorties attempted (only 133 to the Maquis area) 275 were deemed successful (60 with regard to the Maquis). SOE now estimated that taking into account February and March as well, arms had been provided for approximately 65,000 men over the whole of France.

On the night of Easter Sunday, Dennis Field’s crew continued with their efforts to arm the French Resistance forces. The trip to the drop point was without incident, and the arms cargo released on ‘target’.

Dennis Field: The return flight progressed equally well as we passed our crossing point on the Loire near to Blois, and I prepared to climb towards the coast. I avoided a train further up the line east of Le Mans as I built up speed and then, past the railway, pulled up the nose. Suddenly at about 2,000 feet, both Jim and Tony shouted, ‘Weave’, but as I rammed the aircraft down into a steep diving turn to port there were loud explosions just behind the cockpit as we were raked down the starboard side by light flak which poured up at us from the train. I kept her down and after a short time the firing, and our gunner’s reply ceased.

Alan immediately came on saying that Charlie had been badly hit in his head, trunk and legs, collapsing over his table, and that Eddie, standing in the astrodome, had been severely wounded in the leg and also in the back. Jim and Tony reported safe and damage-free and I sent Arthur back to help and report. I asked Alan for a course but his charts were covered and ruined by Charlie’s blood and other body fluids. A chunk of shrapnel missed Alan’s head by inches and shattered his Gee set – had he been any taller he would have been decapitated.

I made a quick estimate and steered due north, and then opened to full power, built up speed and started the climb to height. A superficial check indicated that structurally the engineer’s station as well as Alan’s was a shambles; the shrapnel had entered through his side panel, destroying many of the instruments, and a piece of metal had also damaged the pitch lever bracket. Charlie was in a bad way and had been laid on the floor and given a morphine injection, but he still tried to help with advice on controls even though he must have known his chances were slim. Emergency dressings were applied to Eddie’s wounds and he then returned to his station refusing morphia in case it might affect his reflexes, and continued to transmit and operate his set throughout the rest of the flight in spite of severe pain and shock. Whatever else had occurred I did not know, but the engines seemed OK although the fuel position and operation were uncertain because of the damage.

Whilst the wounded were being seen to and the adrenalin-fired gunners remained on full alert, Dennis lifted the Stirling. Within half an hour the Channel was reached and distress signals were sent. Approaching England it became clear to Dennis that he had to land as soon as possible and at the coast there was relief as a flarepath appeared on the edge of some cliffs. Dennis smartly requested permission to land, which was granted, and he prepared to put his aircraft down, conscious of the fact that the flarepath, facing to the sea, looked short, but the needs of his injured crewmates outweighed his concerns. Unknown to the crew at the time they were going to attempt to land a four-engined heavy bomber on the grass runway of a fighter airfield, Friston, near Beachy Head. Further problems arose when Dennis tried to lower the undercarriage. There was no response and Alan Turner had to crank it down by hand whilst the Stirling circled. Finally Dennis could line his Stirling up and begin a landing.

Dennis Field: The green lights finally came on and I came in low touching down on the edge of the grass runway. About half way along, the stretch of lights ahead was rapidly running out and I rammed open the throttles. We were barely above stalling speed as we shot over the cliff edge and I was fortunate to sink fifty to a hundred feet and gain flying speed for a climb but was unable to retract the undercarriage. The second approach and touchdown at minimum speed were similar but this time there was insufficient room for overshoot. I made the instant decision to swing off applying full rudder and brake. The port wing dipped as the aircraft careered round and then the undercarriage collapsed. We thumped to a jarring halt, clods of torn earth flying up from the distorted propellers until I switched them off. No one had been further harmed by the violent arrival and there was no fire. Charlie lay still on the floor and was too injured to be moved inexpertly except in extremis. When I clambered out of the overhead hatch the others were helping Eddie from the rear escape. We carefully lifted him down, moved him clear and made him as comfortable as possible. By now, ambulance and fire engine should have arrived but there was no sign of them so I clambered back over the wing into the cockpit and called up on the R/T requesting in unequivocal terms that they pull their fingers out. They arrived shortly afterwards. The MO [medical officer] gave further first aid and the stretcher party carefully carried Charlie out through the rear door and into the ambulance to join Eddie for the short ride to Eastbourne hospital.

Dennis and the rest of the crew remained at the fighter station for the night. Early the next morning they went to the hospital.

Dennis Field: Our fears were realised when we were told that Charlie had died during the night in spite of massive blood transfusions. Eddie had undergone surgery to remove shrapnel from his leg and back. We were allowed to see him and he managed a joke about the large chunk of metal in a bottle by his bed, and which had lodged in his shinbone. Throughout their ordeal Eddie and Charlie had displayed extraordinary courage and fortitude. We left the hospital in sombre mood and went back to Friston to recover any important movables left in the aircraft.

The airmen caught the train to London, staying in a force’s hostel for the night, and the next day, via tube, bus and train, returned to Tuddenham.

Dennis Field: It was perhaps typical of the times that five scruffy, hatless, unshaven aircrew carrying parachutes and helmets and one with his tunic covered in dried blood excited not a glance or comment let alone offer of a lift or assistance.

Eddie Durrans courage during the incident described would later be acknowledged with the awarding of the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.

(Flight Engineer Charlie Waller is now buried at Brookwood Military Cemetery, Grave Reference 20. C. 8.)

Thank you, Steve, for posting this story on the 80th anniversary of the tragic sortie undertaken by Dennis Field and his crew on 10 Apr 1944. My father-in-law Alan Turner was the navigator in Dennis’ crew.