This evening, 6/7 March, marks the 80th anniversary of the opening of Bomber Command’s direct support to operation Overlord, exactly three months before the 6th June, D-Day, sea and air assault on the Normandy beaches. What follows is an extract from my book D-Day Bombers, describing the events that night.

On 4 March 1944 Air Vice Marshal W.A. Coryton (Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Operations)), issued a directive to Commander-in-Chief Bomber Command Sir Arthur Harris concerning targets for attack by his forces prior to Overlord:

‘Sir, I am directed to inform you that a review has been made of targets for attack by Bomber Command during the present and forthcoming moonlight periods. The purpose of this review is to provide targets, the attack of which is most likely to be of assistance to ‘Pointblank’ and ‘Overlord’ either through the actual destruction of supplies and equipment of use to the enemy or by providing opportunity to obtain experience of the effects of night attack of airfields, communication centres and ammunition dumps, before operation ‘Overlord’.’

Initially the attacks were an experiment. The use of ground-marking techniques was specified, and the directive specifically stated that analysis of the raids would provide data to assist in the planning of Overlord.

On the night of 6/7 March 1944 RAF Bomber Command sent 261 Halifaxes and 6 to the railyards at Trappes. Harris’s airmen were under scrutiny. Their commander did not believe, or did not want to be shown publicly believing, that they had the weaponry or ability to achieve the necessary degree of precision. His airmen would prove him wrong.

Just after 8.30 p.m. on the evening of 6 March 1944, Squadron Leader Stephens, piloting his RAF Bomber Command 109 Squadron Mosquito over German-occupied France, received his call sign, to begin his run-in to a target he was to identify and mark for the heavy bombers that would follow.

At 2042 hours two caskets, each weighing 250 lb fell from the bomb bay of Mosquito LR500, flying at 26,000 feet. The aim had been good; the first of these target indicators (TI) fell 70 yards from the aiming point, the second 140 yards.

Thousands of feet above the target, bomb aimers had been peering through the nose blister of their four-engined Halifax bombers, searching the darkness below for the red markers they had been told about at briefing. Once the markers burst into life the bomb runs could begin; each Halifax pilot lined up his aircraft, following his bomb aimer’s instructions, such as ‘Left, Left steady, steady’ and then ‘bomb’s gone’, and the explosives plummeted to the target.

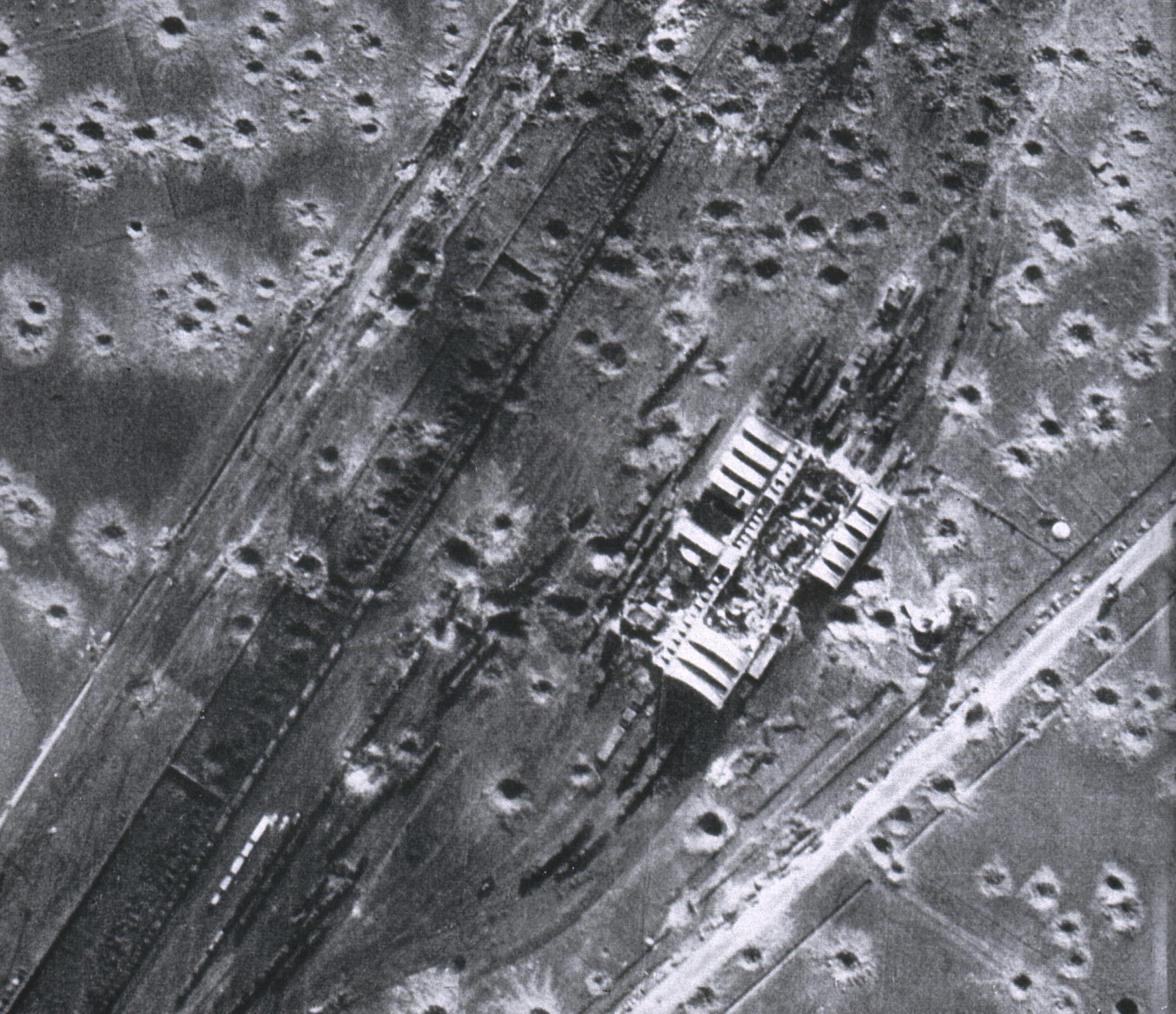

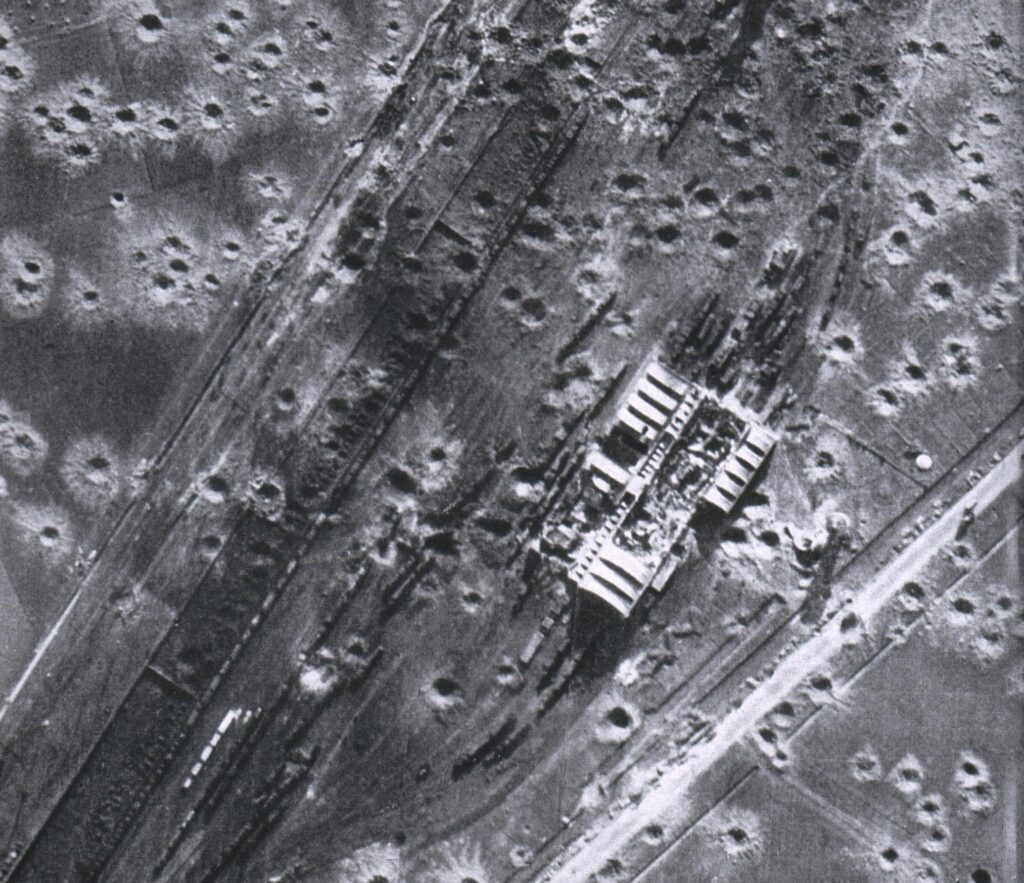

Soon more TI burst below, dropped by another Mosquito. In the space of approximately 30 minutes 2,046 bombs totalling 699 tons fell on the railway marshalling yards at Trappes. Just after the attack on the western section of the railyards had finished, a 109 Squadron Mosquito lined up on the eastern end of the Trappes railyards. At 2114 hours two TI fell from the Mosquito and the heavy bombers came in. In the next 20 minutes two further salvos of red TI marked the target and 1,582 bombs, weighing 555 tons, ripped up tracks, wrecked rolling stock and tore down engine sheds.

In the early hours of 7 March 1944 all the RAF Bomber Command aircraft returning from the raid to Trappes landed safely in England. They had experienced little opposition on their excursion into northern France. Only two engagements with enemy aircraft were reported and one of these was found to be friendly fire from another Halifax.

The very next day following the Trappes attack an RAF 541 Squadron Spitfire took off from Benson, arrived over the railyards, photographed the area and sped back to base in England. Two days later a further reconnaissance sortie returned with photographs of the railyards.

The RAF Bomber Command analysts could be well pleased with the bomber crews’ efforts. Extensive damage was apparent across the railyard and 190 hits were counted as directly on the tracks. Fifty bombs fell on rail lines carrying rolling stock, derailing and destroying many of the wagons. There was further damage to engines, engine sheds, electric lines and footbridges. The raid was a clear success but there had been one disturbing outcome. To the north-west of the target area bombs had fallen on French houses, killing and injuring civilians. In the context of RAF Bomber Command operations carried out in previous years, this raid could be deemed very accurate. Nevertheless the proximity of the target to residential areas meant there was always the risk of friendly civilian casualties. But, in terms of the desired outcome of the war, the Allies would deem this risk not only necessary, but acceptable.