Bomber Command Navigator Roy Smith sadly passed away on 1st August 2019. In the picture above Roy is standing second from right, in front of his Stirling ‘Jolly Roger’.

In January 2018 I had the privilege of speaking at Roy’s Legion d’Honneur award ceremony. With the agreement of Roy’s son Peter and daughter Ness, here is a transcript of the speech which outlines Roy’s remarkable flying days.

Legion d’Honneur Ceremony – 13th January 2018

Good afternoon and firstly a thank you to Roy and his family for affording me the privilege to speak about his Second World War career at such a significant occasion. It has been a really interesting process putting together Roy’s story and thanks to Ness for providing the raw details and also to acknowledge the use in this speech of some of Roy’s granddaughter Katie’s work.

The Legion d’Honneur, as we know, was awarded in recognition to those who operated in support of the Normandy Landings in June 1944. Roy’s Bomber Command service could be seen to have stretched over three distinct campaigns, one of which had, what could be called, an indirect influence of the success of D-Day and beyond, the second which directly affected the outcome of that campaign, and a third which was in direct defence of the population of the United Kingdom.

Roy was one of thousands of young airmen who volunteered for aircrew duties with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. And to repeat that he was a volunteer and was not compelled to take to the air. On the day war was declared in September 1939 Roy was actually helping a friend build a shelter in his garden ‘Halfway through the operation the air-raid sirens sounded which led everyone to increase their efforts anticipating that we were about to be bombed.’ However the period known as the Phoney War followed, but through late 1940 and 1941 the Luftwaffe Blitz certainly brought home the realities of war. In early 1941 Roy decided he needed to take an active part in the struggle, initially favouring the Navy, but his work with a telephone company was deemed essential and he was told the only opportunity available to him was aircrew. He filled out the forms and was called up in September 1941, having expressed an interest in being a navigator. Which we all know, of course, is the most important member of any crew.

What followed then was a familiar journey for so many young men who had volunteered for aircrew. The basics at Lords Cricket Ground in London, then Initial Training Wing, and eventually a trip overseas to learn to fly away from the hostile airspace over Europe. Roy ended up at Turner Field in Georgia, USA, and was somewhat surprised to discover that he was actually on a pilot’s course. To quote Roy:

‘I don’t think my heart was in this aspect of flying, I still felt I wanted to be a navigator. However things worked out because I didn’t successfully complete the course although it was nothing to do with flying capability. It happened one evening, I went out with two or three others – I imagine we had quite a few beers and I got separated from the others. I eventually found a taxi but did not arrive back at camp until after the permitted time. Knowing that this would be a disciplinary offence, and that I would in all probability be removed from the course, I decided to try and enter the camp by squeezing under the surrounding wire fence. During this operation I heard the sound of a rifle shot, lights were switched on and I was caught – that was the end of my pilot training and I learnt that I would be sent to Canada on a navigator’s course – so I was not particularly disappointed.’

During the second half of 1942 Roy developed his navigator skills in Canada, and by the end of the year he was back in the UK. Further training followed and in the Summer of 1943 Roy formed up with his crew, mainly New Zealanders, and they began to familiarise themselves with flying the four-engine Stirling aircraft. Those who flew the Stirling have an affection for their aircraft, but it wasn’t, how shall we say, the best four-engine heavy bomber the RAF had in service. In fact it was getting a reputation as a ‘flying coffin’ when it came to Main Force operations over Germany. Despite limitations however it would be called upon to fulfil other vitally significant tasks. In September 1943 Roy and his crew arrived at No. 199 Squadron, Lakenheath, about to fly operationally in Stirlings, amidst what became recognised as one of the most hostile air battles ever.

Bomber Command had, since the start of the war, seen dramatic changes in regard operational capabilities and its role. Quite early on unsustainable daylight losses had resulted in the bomber campaign being almost exclusively carried out at night. And the efficiency of crews to find targets and bomb them accurately had been questioned. However new technological aids, such as the Gee set, and H2S radar (terms which will be very familiar to Roy), better aircraft and training, steadily improved the command’s capabilities. By the Summer of 1943 Bomber Command was fighting a battle of attrition over Germany, and when Roy entered the battle if was about to reach an unprecedented level.

Unfortunately Roy had to miss the first couple of flights with his original crew owing to a severe migraine. So a change of crew followed and he soon flew his first operation, minelaying, or gardening as they called it, with a new crew and Australian skipper, Allen Noble. The scale of Bomber Command’s minelaying activity should not be underestimated, Bomber Command’s Commander in Chief Sir Arthur Harris wrote in his post-war memoir that over 1,000 enemy ships were sunk or damaged as a consequence of the minelaying.

It might also be worth mentioning luck at this stage, something aircrew’s regularly talk about, and to which they owe their survival. On 4 March 1944 Roy’s first crew were shot down, three of the crew lost their lives, three men became POWs and one evaded back to the UK. Also, as Roy recalls:

‘I think it was shortly after moving in that most of us began to have doubts about our future as within a week or two we woke to find seven empty beds. A few days later a replacement crew joined us but three weeks later they were gone. We used to try and put on a brave face and make facetious comments, e.g. “Can I have your bike if you don’t make it tonight?”- but at the same time hoping against hope that we would wake to find everybody safely back.’

In late 1943 and early 1944 Roy and his crew were operating over German airspace in what became known as Bomber Command’s Battle of Berlin. Roy would visit the ‘Big City’ but primarily he flew mining operations, although in January 1944 he also took part in raids against strange constructions that were being erected all over Northern France. These were in fact V1 launch sites, which had recently been identified and Bomber Command had been tasked with carrying out a series of experimental raids against these to test out the most effective way of destroying them. The Stirling squadrons were called upon. These raids did have an effect of the German secret weapon plans and resulted in a change of strategy, which I would argue would go on to limit the scale of attack on the UK when the V1s started crossing The English Channel in June 1944.

In regard to Berlin, Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command Sir Arthur Harris said to his crews ‘Tonight you are going to the Big City. You will have the opportunity to light a fire in the belly of the enemy that will burn his black heart out.’ He required his airmen to fly deep into unfriendly airspace and bring the war direct to the German Nazi capital Berlin. From the autumn of 1943 to the last days of winter in early 1944, during the hours of extended darkness, the bomber crews braved the flak, the searchlights, enemy night fighters and extremes of weather, to bombard the ‘black heart’. But the costs were high. Across 19 attacks on Berlin there were 10,813 sorties, with 625 aircraft losses. The human cost in terms of airmen involved in these raids were 2,690 deaths, 987 men captured, 34 evaders and 18 men interned in Sweden. Here is Roy talking about the raid to Berlin on 23 November 1943:

‘We set off for Berlin and although we did not know it at the time this was to be the last time that Stirlings were to be used on main targets. Fifty Stirlings out of a total bomber force of 764 were used on this particular raid mainly Lancasters and Halifaxes: of the total 26 did not return, a percentage loss of 3.4%. Of these, five were Stirlings – a loss of 10%. This may not seem excessive but to complete a tour you had to do this thirty times. Stirlings were most susceptible to losses insofar that being five or six thousand feet below the main force we were one of the first to be coned. This attracted German fighters and it was then that Chess our rear gunner, took command. I can still hear him instructing Allen the pilot “ME on the port quarter 500 yards – 450 yards – get ready to corkscrew port – corkscrew NOW”. German fighters used cannon with a range of 400 yards – our gunners had machine guns with a range of 200 yards. The idea was to judge exactly when the fighter would open fire – too early and the fighter would follow you down – too late you would probably be hit.’

Roy and his crew were lucky that night, a raid which actually proved to be the most effective raid on Berlin of the entire war. But were the losses sustained during this Battle of Berlin period worth it? It was, in my view, a significant step towards victory in Europe. It did create a ‘front’ in the skies over Germany that drew on the enemy’s resources in terms of manpower, aircraft and ground defences. These were resources that could not be brought to bear on the Russian front, or in the Mediterranean theatre. And the German requirement to defend the skies above the Reich against the RAF and American air forces certainly played a part in the future success of the June 1944 Normandy beach landings, allowing the Allies time to establish their foothold in Europe under an umbrella of local air superiority.

I’m going to share a few more of Roy’s experiences when operating during this period. Such stories will be familiar to many veteran aircrew. The risks involved, the hope that lady luck was on board that day.

‘An engine caught fire over the Midlands when returning from one of our trips. Allen instructed all crew members to assemble at the escape hatch and be prepared to jump when instructed. In the meantime he had put the plane into a steep dive and managed to blow out the flames. I am not sure, had he been unable to do this, that he would have got out.’

I recall when interviewing Roy a year ago his eyes light up when he mentioned Allen Noble. Clearly he held him in high esteem. The crew bond formed through teamwork and survival, as Roy recalls, ‘A friendly crew, all being keen, conscientious and driven by the desire not to let your comrades down’. Another incident recalled by Roy:

‘We were routed over N.W. London but it seems that the ground defences were not informed and we were subjected to some anti-aircraft fire. George our wireless operator, fired off the colours of the day to no avail. As a precaution someone opened the hatch in case we had to make an emergency escape. Our mid-upper gunner bent down from his turret to see what was going on and seeing the hatch was open switched on his intercom to contact the pilot. However when bending down he must have pulled his intercom plug slightly out of the socket so there was no connection to the other crew members. Having seen the open hatch and being unable to contact anyone, he assumed that we had all jumped and quickly followed suit. We were given to understand that he landed in Walthamstow and his parachute had caught on some railings leaving him suspended a foot or two above the ground.’

‘Another memorable incident involved a mining trip. We were routed out over Selsey but prior to reaching the coast we lost an engine and one of the remaining three was not functioning too well. Allen decided that the only chance of getting back was to continue on to clear the coast, drop the mines, and to let as much of our fuel go, just saving enough to get back to base. Having done so we were still losing height and there was no chance of getting back to East Anglia. It was decided that we would try and get in at Dunsfold. As we approached the runway there appeared to be a large black cloud about one mile before the beginning of the runway. Allen was not sure if he could get over the top or whether he should try and get underneath, but height was precious, and a decision was made to go over the top. This decision was supported by the fact that the electrics which controlled the undercarriage were dependent on the engine that had failed, and the undercarriage had to be wound down by hand. Each side had to be fitted with a cranked handle and four of us – two each side – had to wind at maximum speed changing over with our partner every 30 to 60 seconds. The official time to complete the operation is 5 ½ minutes – I don’t think we took more than 3 minutes. We just managed to lock each undercarriage in the down position two or three seconds before they touched the runway. What a relief, but not such a big relief as we experienced after getting out and looking back to see that we had not skimmed the top of a black cloud but a forest of tall trees. We celebrated our good fortune by going to Brighton, having a night out, sleeping on the floor at Chess’s house and returning to Dunsfold the next morning.’

The Battle of Berlin officially ended in March 1944 but by then Allied attention was already shifting towards the support of Operation Overlord and the re-entry into Europe via Normandy. One of the key elements to success was for the Allies to gain a footing on the beaches, and then establish a beachhead from which to breakout. The Germans would be trying to throw the Allies back in to the Sea. It was what became known as the Battle of the Build Up. The Allies had to get sufficient resources and manpower ashore to secure their position before the Germans could reinforce their coastal troops. Bomber Command was tasked with hindering German inland movement and reinforcement and one key element was to supply the French Resistance and the Maquis with arms and armour by which they could engage German troops, blow bridges, rail lines, and block roads. Specific squadrons in Bomber Command were detailed including 199 Squadron. Roy’s main task in this period was to direct his crew across a hostile country, during a blackout and basically find a field to drop supplies. A quite remarkable achievement. Roy recalls these sorties:

‘Some of these were in the southern part of France and involved a return flight of about 8 hours. We usually crossed the French coast of Brittany at about 8 – 10,000 feet and dropped down to 2,000 feet or less on reaching the Loire. The low height was supposed to be safe insofar that it made it almost impossible for an enemy fighter to attack from below and dangerous to attack from above, having insufficient height to get out of a dive. We were of course lower than this when making a drop and on the return from one trip one of the ground crew found a small piece of branch in the tail wheel.’

There is no doubt that the Resistance’s efforts compromised the German ability to reinforce the Normandy battle – a direct consequence of Roy and his colleagues efforts to provide them with the weaponry they needed. A quick statistic, in March 1944 487 tons of equipment was delivered, including almost 5,000 rifles, 40,000 grenades, 10 million bullets. And across February and March arms for 42,000 men had been supplied. In addition to these Resistance sorties Roy was also involved in two operations bombing French railyards, in March 1944, a direct attempt to block the rail lines through which German reinforcements would attempt to reach the battle. Following the 6 June 1944 D-Day landing the Allies would win the Battle of the Build Up and would break out from Normandy and liberate France. Roy had done his bit, he had supplied the Resistance, he had blocked some of the railywards. In addition, a week after D-Day the Germans also launched their V-weapons campaign against England and the Stirling squadrons were called in to bomb some of the launch sites, thereby reducing the numbers of V1s that could be launched – a campaign in direct defence of London and the home counties. And I should also mention that Roy was involved in sorties whereby window was dropped, strips of aluminium foil, which would confuse German radar and seriously hinder the German’s ability to track RAF bomber streams.

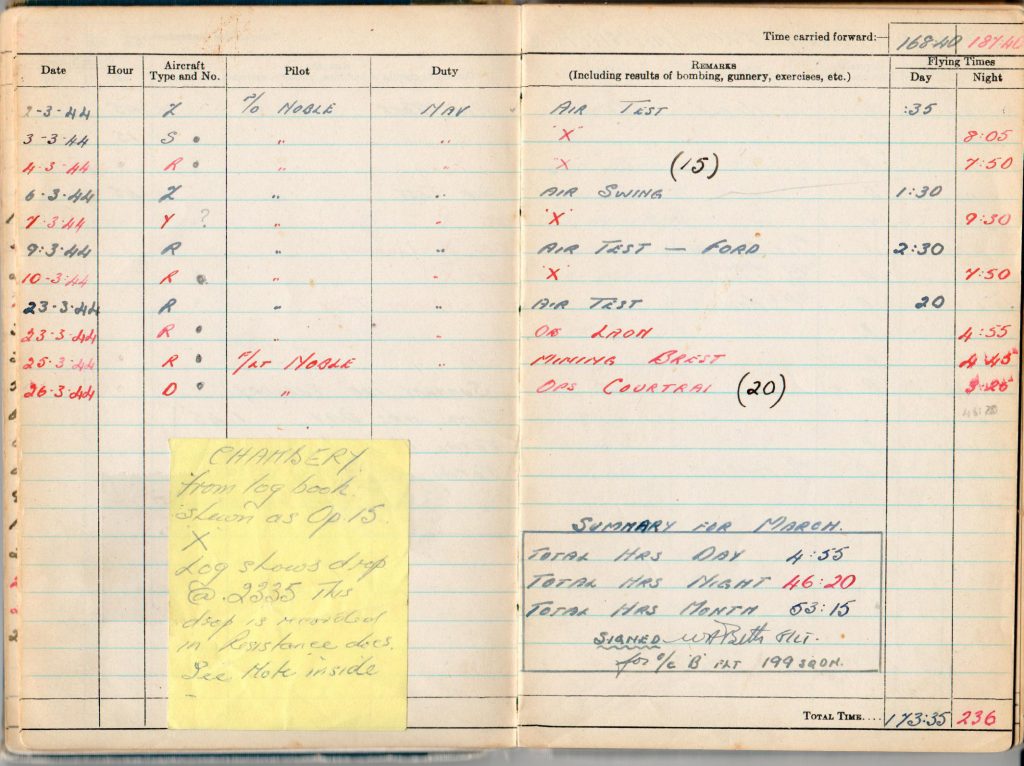

In July 1944 Roy and his crew reached the end of their tour of 30 operations but, as a competent and experienced crew, they were given the opportunity to carry on and eventually Roy would complete 42 operations. A remarkable number of operations, against the odds, 60% of Bomber Command aircrew became casualties, carried out with great skill and bravery. If you get a chance have a look at Roy’s extraordinary set of navigational logs and imagine him sitting at his desk, for hours on end, filling these out in a four engine heavy bomber laden with explosive fuel, oxygen and bombs, while being shot at. Roy’s service, as recognised by the award of the Legion d’Honneur today, directly impacted the outcome of the battle in Normandy in 1944, the liberation of France and the eventual total defeat of Nazism. 199 Squadron’s motto was ‘Let Tyrants Tremble’. Roy and his colleagues not only made one tyrant in particular tremble, they were instrumental in that tyrant’s downfall and the destruction of one of the most evil regimes in History. We live in freedom – thank you Roy.

Hi Steve

I think I contacted you a few years ago about my Dad, Flt Lt Ron Carpenter DFM. He completed a tour of ops on 10 Sqn Halifaxes and 13 ops on 223 Sqn Liberators. Dad knew Roy Smith very well. They both grew up in Hornsey, N London. Dad’s brother married Roy’s sister. Unfortunately she died at an early age.

My parents were friends for many years with Roy and his wife and I met Roy many times. A very nice man

Regards

David Carpoenter