There are many churchyards the length and breadth of the United Kingdom that host the final resting place of Royal Air Force airmen. For many, but by no means all, their graves are marked with the distinctive, simple, outline of a white headstone; provided by that extraordinary organisation – the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. To the east of Willian (All Saints) Church, near Letchworth, Hertfordshire, is one such headstone marking the grave of one of Winston Churchill’s ‘Few’, Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot Gordon Mitchell.

Dawn, 11 July 1940. Having spent the night at RAF Middle Wallop, Spitfire pilot Gordon Mitchell accompanies fellow No. 609 Squadron colleagues on the short flight to RAF Warmwell, a few miles inland from the Dorset coast. Having landed, they await the call to scramble, to take-off and counter any Luftwaffe incursions. Their wait is short.

In the early 1930s Cambridge University Air Squadron gave Gordon the opportunity to fly. And when not in the air, or studying law and economics, he proved an accomplished sportsman. Not only as a member of the Queens College tennis team and a Cambridge Blue, but also representing Scotland at Hockey. In 1933 Gordon travelled abroad to work in Sarawak, and on return to England a few years later he once more took to the air, with the Auxiliary Air Force, obtaining a commission with No. 609 ‘West Riding’ Squadron in November 1938.

With the threat of war with Germany becoming reality, Gordon was sent to hone his flying skills at No. 6 Flying Training School, Little Rissington. Rejoining 609 Squadron on 5 May 1940, he built up experience on the squadron’s Supermarine Spitfires, and transferred with his colleagues from RAF Drem to RAF Northolt, the squadron diarist recording on 19 May the unit as ‘available’ by 1300 hours, and a congratulatory message on the ‘speed of move’ from the Air Officer Commanding No. 11 Group Keith Park.

The RAF’s fighter aircraft were in demand. On 10 May Germany launched the invasion of France and the Low Countries. The Allied forces failed to counter the Nazi ‘Blitzkrieg’ and at the end of the month 609 Squadron joined the air cover supporting the desperate evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk. Gordon played his part in an operational patrol over the beaches on the first day of June, the next day carrying out an evening sortie with three of his fellow 609 pilots, the squadron diary recording their role as above guard for No. 72 Squadron as ‘very effective … 72 Squadron were able successfully to attack enemy bombers while the escorting fighters, which were above our squadron, did not dare go down to the rescue.’ The next day the diary recorded, ‘It is learned that the Dunkirk evacuation is practically complete.’

On 4 June British Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed the House of Commons. He was defiant. ‘We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender’. But the situation in France deteriorates. On 11, 12, and 13 June Gordon flew his Spitfire over France as he and squadron colleagues escorted Winston Churchill to Anglo-French Supreme War Council meetings. Within days the French Government capitulated to German aggression. All that stood between England and invasion is the English Channel and Churchill once more addressed the House of Commons, ‘… the Battle of France is over … the Battle of Britain is about to begin.’ But there is a pause. The German armed forces needed time to recover from their losses in the Battle of France, giving the Royal Air Force, in particular Fighter Command, time to regroup and prepare.

July 1940 and the Luftwaffe began to test the British defences, attacking seaborne convoys steaming along the south and east coast of England. Carrying vital resources, the shipping must be protected, and many an RAF fighter pilot found themselves patrolling in defence of such convoys. On 4 July No. 609 Squadron received orders to move to RAF Middle Wallop in Hampshire, with operational flying from the satellite airfield at RAF Warmwell, a few miles inland from the Dorset coast. The squadron diary recorded on 7 July, ‘one flight only of 609 Squadron will be at ‘readiness’ at Warmwell during the hours of daylight. The Squadron will be based at Middle Wallop, and the pilots will sleep there each night.’ In the past two days Gordon had flown patrols over Portland. On the 8 July he was airborne at 1030 hours for an ‘Investigation – Angels 10’, landing at 1130 hours. Then taking off at 1455 hours to patrol Portland Bill, landing at 1545 hours. On 9 July the squadron diarist noted, ‘It is anticipated that the pilots will be relieved of the present intense state of preparedness after about one week … In the evening, at Warmwell, Green Section intercepted a raid over Portland and F/O Drummond-Hay failed to return. It is assumed that he is dead.’ That assumption proved correct and Peter Hay-Drummond-Hay is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

Historians deem the Battle of Britain to officially open on 10 July with raids on convoys off North Foreland and Dover, during which 13 German aircraft and 6 RAF fighters fall. Gordon Mitchell played a minor role that day with a short but uneventful patrol over Portland in the afternoon, and then a similarly uneventful twenty-five minute flight to investigate a ‘sound plot’ in the evening. Early the next day it appeared that the Luftwaffe was preparing for another scrap over the sea, in which Gordon and his squadron colleagues would scramble to oppose them.

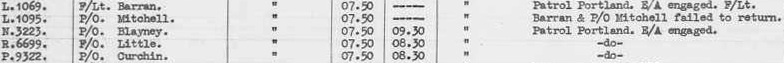

0730 hours, 11 July 1940. Radar picks up a contact in the direction of Portland, on the south coast of England. Aircraft from Luftlotte 3, flying from the Cherbourg peninsula, have set out to attack a shipping convoy in the Lyme Bay area. Earlier, at dawn, 609 Squadron had sent some of its Spitfires from Middle Wallop to Warmwell. The call comes through to take to the air and patrol off Portland, and at 0750 hours five Spitfires flown by Philip ‘Pip’ Barran, Gordon Mitchell, Jarvis Blayney, Bernard Little, and John Curchin are airborne.

Fifteen miles south of Portland the 609 Squadron pilots find their enemy – Junkers 87 Stuka dive bombers, in line astern, preparing to strike a ship. ‘Pip’ Barran orders his colleagues to turn and position themselves between the sun and the bombers. The thirty-one-year-old leads Blue Section, three aircraft, in line astern, into the attack, whilst Green section, two aircraft, weave behind acting as rear guard. But they have fallen into a trap. As the attacking Spitfires home in, Blayney, flying as Blue 3, has his attention grabbed by bullets fizzing past his windscreen. He has little choice but to abandon the attack on the Stukas, and take evasive action, broadcasting a warning to his colleagues. Having carried out a sharp turn he finds himself free of danger. Blayney scans the sky, sighting a Ju87 at 1,500 feet. He seizes the moment, opens fire at 200 yards, closes to 50 yards, and his 2 to 3 second burst hits home. The Ju87 zigzags into the sea. With no further enemy aircraft in sight Blayney remains above the bombed ship but catches sight of Blue 1, ‘Pip’ Barran, making for the English coast, fire and smoke belching from his Spitfire. Blayney turns and follows until he sees Barran’s engine stop a few miles south of Portland Bill. Barran bales out, floating down into the sea. He is later picked up by the Navy but dies owing to the severity of his burns.

Meanwhile the pilots in Green Section, to the rear, are flying and fighting for their lives. Green 1, Bernard Little, suddenly finds himself amidst a swarm of Messerschmitt 109 fighters, and notices Blue Section under attack. Little throws his aircraft around the sky, and then starts mixing it with some Ju87s. As one of the Stukas dives toward the sea Little unleashes his guns, the quick burst striking home. The 609 Squadron pilot has no time to watch and see if his foe plunges into the water, such a distraction could prove fatal, but he later reports that his adversary fell, inverted, with small pieces breaking away.

In the melee Green 2, John Curchin, has also managed to get behind a Ju87, but alarmingly becomes aware of two Me109s on his tail. He sends his Spitfire into evasive manoeuvres and by the time he has lost the fighters the Ju87s are nowhere in sight. Curchin sees enemy fighters 10 miles away, and then a pilot, undoubtedly Pip Barran, baling out from a burning Spitfire. Curchin, Blayney and Little return home to tell of the fight. News of Barran’s death soon comes through. But what of Gordon Mitchell? He was part of Blue Section but has failed to return, and the 609 Squadron Intelligence Officer obtains little information from the other pilots. Gordon is recorded as missing and for a few days no news comes through as to his fate. Eventually his death is reported – his body having washed ashore at Newport on the Isle of Wight. (Gordon had been shot down by Luftwaffe pilot Oberleutenant Dobislav of III/JG27 flying a Messerschmitt Bf 109E).

Gordon Mitchell’s funeral is held on 25 July 1940. 609 Squadron’s experiences on the morning of 11 July form part of Fighter Command’s steep learning curve in the early days of the Battle of Britain. The 609 Squadron diarist pulls no punches in recording his feelings on the tactics used.

The utter futility of sending a very small section of fighters to cope with the intense enemy activity in the Portland area is bitterly resented by the pilots. The fact that they have so often been sent off to make an interception – as a Section, or possibly a Flight – only to find themselves hopelessly outnumbered by enemy fighter acting as guard to the bombers, is discouraging because the British fighter then finds himself unable to do his job of destroying the bombers, and is compelled to fight a defensive action. The situation is keenly felt by this Squadron, whose ‘score’ of enemy aircraft is in too close a ratio to its own losses. It is felt that we happen to have been particularly unlucky in that both at Dunkirk and at Portland our contacts with the enemy have taken place when the numerical odds were rather too unreasonable.

One member of the squadron also ‘keenly felt’ Gordon Mitchell’s loss. In his book Spitfire Pilot 609 Squadron pilot David Crook DFC recorded his feelings.

Gordon’s death in particular made a deep impression on me, because I knew him much better than I knew Pip. We were at school together, and he, Michael, and I had spent the whole war together, and were so accustomed to being in each other’s company that I could not then (and still cannot now) get used to the idea that we should not see Gordon again or spend any more of our gay evenings together or rag him about the moustache of which he was so proud. He was a delightful person, a very amusing and charming companion and one of the most generous people I ever knew, both as regards material matters and, more important still, in his outlook and views. He was also a brilliant athlete, a Cambridge Hockey Blue and Scots International. It always used to delight me to watch Gordon playing any game, whether hockey, tennis, or squash, because he played with such a natural ease and grace – the unmistakable sign of a first-class athlete. He could not have wished to die in more gallant circumstance.

Sources: 609 Squadron Operation Records Book, Commonwealth War Graves Commission website (www.cwgc.org) D.M Crook’s Spitfire Pilot, Ken Wynn’s Men of the Battle of Britain and Derek Wood and Derek Dempster’s The Narrow Margin. Thanks to the following for help with this article: Chris Goss, Joss Leclercq, David Darley, Hugh Mulligan and Dr. Beverley Webb who tends Gordon’s grave.